Filmmaker Focus: Em Weinstein

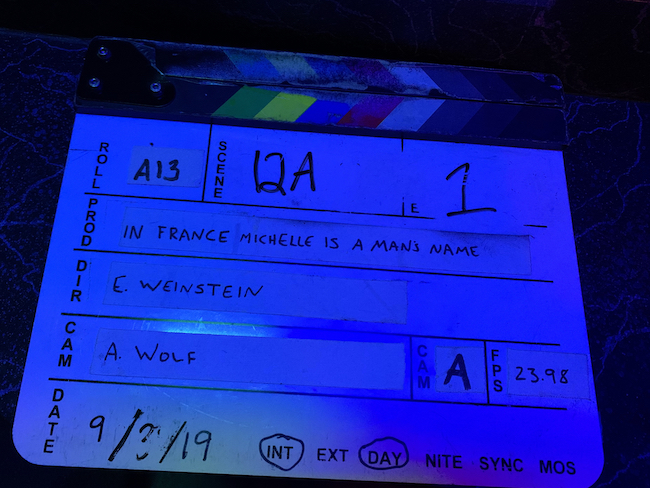

Writer-director Em Weinstein’s short film In France Michelle Is a Man’s Name premiered in August at the Outfest Los Angeles Film Festival, where it was awarded the Grand Jury Prize, U.S. Narrative Short. Shot on location in Oregon, the film focuses on Michael (Ari Damasco), a young trans man who returns to his rural home and attempts to reconnect with his mother and father (Olga Sanchez and Jerry Carlton, respectively). Following an uneasy dinner, Michael joins his dad for a drive, but their early bonding soon gives way to a chasm of misunderstanding.

Sponsored by Panavision and Light Iron, the Grand Jury Prize was accompanied by a grant for a Panavision camera package and Light Iron finishing services that Weinstein can use on their next project. “Finding out about the award was such an amazing gift,” Weinstein shares. “It felt like this incredible affirmation that this movie had been seen and that it had had an impact, which is all we really wanted when we made it.”

Panavision recently spoke with Weinstein about the film, their inspirations, and what might be next for the writer-director.

Panavision: At what point did you know you wanted to make a career of telling stories as a writer and director?

Em Weinstein: My mom is a playwright and an actor, and I grew up watching her work and sitting in her greenrooms in little downtown New York theater spaces. I had thought I wanted to be an actor, but when I was 10 years old, I had surgery for a brain tumor and was bedridden and in a wheelchair for many months. I started to write from my bed, and I wrote my first play, a comedy called A Fly in My Soup. It was not good. [Laughs.] But from then on I knew I wanted to be a writer and director, and I’ve been aiming for this ever since.

Film came to me only recently. I was in grad school for theater directing at Yale School of Drama, which is a very theater-focused directing program, and I found myself hungry to tell stories in different ways and to reach audiences I felt my plays weren’t reaching. So I made my first short when I was at grad school and have been focused on filmmaking as well as theater since then. In France Michelle Is a Man’s Name felt like my first major foray into cinematic storytelling because it is so visual and has so few words. It felt like I wasn’t using the same toolkit as I did as a theater director.

Were there any particular stories that inspired you in those early days?

Weinstein: I went to a Shakespeare camp in Mount Washington when I was in second and third grade; I completely fell in love with Shakespeare from about age 7. He has been the storyteller who’s inspired me the most. Especially as a nonbinary gender-questioning human being, I’ve found so much of myself in his stories, which are extremely queer. I find the way he conceptualized gender to be quite radical and forward thinking, especially in his plays where men play women playing men. His ideas around the fluidity of gender identity and sexuality probably inspired me without my realizing it as a little kid, and they continue to.

Have you had any mentors along the way?

Weinstein: I continuously find mentors in unexpected places. I directed a production of Twelfth Night with teenagers this year, and I was so inspired by the kids I worked with — and every time I teach I feel like I’m being mentored by the students. I had a philosophy professor named Nalini Bhushan in college who completely blew my mind around what thinking is and what literature is. And my mom is an amazing playwright who mostly does social-justice work in the theater now; she’s been a great mentor for me.

There’s also an incredible Russian theater director named Dmitry Krymov. When I was in grad school, he would come and visit once a year and teach us about visual storytelling onstage. He really believes in the power of telling a story with very few words. He’s taught me a lot about being a filmmaker — even though he’s never made a film.

Is there a balance you hope to maintain between theater and film?

Weinstein: Right now, theater is not happening in the same way that it was, but I do hope to find a balance. I hope to bring some of what I’ve learned as a filmmaker to my theater practice because I want theater to be more visual. I think theater can learn so much from cinematic storytelling. But I hope to always do both. I’ve also been working a little bit in television as a writer this year and have found a lot of joy doing that. I want the boundaries between all of these to be more flexible, and I think potentially that will happen in these times of necessity, when theater has to end up looking a lot more like a movie because we’re watching it on a screen.

Your cast for In France Michelle Is a Man’s Name is incredible. Ari Damasco delivers such a brave performance as Michael, and Jerry Carlton brings such depth as his dad. How did you find them?

Weinstein: I worked with this great casting director out of Portland, and the entire cast except for Ari were Portland-based. There were really wonderful actors who came in for the dad, but the movie made complete, new sense to us after watching Jerry perform. He put his all into this movie, and in really tough circumstances. We had a three-day shoot, and it was pouring rain. He worked so hard and was so loving and gave Ari so much.

Ari is a non-actor. We went to college together and he’s one of my best friends. He had acted in a couple of my plays in college and then had gone on to do other things. I thought he would be amazing, and not only did he show up and do a great job, when the s--- hit the fan — as it does on a short film — he held the whole team together. Everyone saw how hard Ari was working, how brave he was and how much love he was giving everyone, and that pulled everyone together and inspired the whole team to work extra hard. He’s an amazing friend and person, and so talented. His soul comes through onscreen, which is a beautiful thing. I’m so grateful to him.

You were working with cinematographer Alexa Wolf, who also shot your first short film, Candace. How did the two of start collaborating?

Weinstein: I found her on the website for Cinematographers XX. We really had no money to make Candace, but I wanted to work with someone amazing, and I somehow convinced Alexa to do it. She’s an amazing collaborator. I loved her commitment to the movie, even if it meant she was telling us a truth we didn’t want to hear. That was really inspiring to me. She’s a professional, and she’s also a badass. She works her ass off and is a true artist. So it was really exciting to reunite. We push each other to do better and to make the movie as good as it can be.

Were there any particular visual references that you and Alexa discussed as you prepared to shoot In France Michelle Is a Man’s Name?

Weinstein: We had so many pictures in our look book, and we actually made a shot list where we had images we wanted to replicate — the first shot is a reference to The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. And there were others like Y Tu Mamá También, Tom at the Farm, My Own Private Idaho, Lady Bird, Once Upon a Time in the West and Days of Heaven. But instead of referencing a whole film, we tried to just reference shots; we would try to replicate a moment or capture the feeling of a specific sequence. We had so many different locations, and the palette changes so much when they go into the strip club, but we wanted to unify everything and make it feel naturalistic. Finding these super-specific visual references for each shot was very helpful.

You make great use of wide lenses close to the actors to create a sense of intimacy, and there’s a clearly deliberate approach to when the camera is stable or handheld. Did you and Alexa discuss and plan everything in advance?

Weinstein: Alexa and I very systematically talked through every single shot beforehand, and we had both a visual and philosophical framework for why each shot was the way it was, with the visual references to back up each choice. We did the same thing for Candace, and it was great. The difficulty with this film was that we ran out of time and suddenly, on the fly, had to cut a third of the shot list and figure out what we needed, what we didn’t and what we could combine. But because we had done all that work, we had a philosophical framework for making those choices, and we were able to pull it off and get what we needed. But it was terrifying, and I think both of us were frustrated! [Laughs.] There were a lot of additional shots that we wanted to get. But that’s part of the joy of filmmaking, and especially the joy of making shorts. You learn on the fly.

There’s a scene with the dad and the son in the truck, and it’s just one shot. That was not how it was supposed to be at all — I think we had planned for six different shots — but it was literally the only thing we could get before we lost the light. I’m so happy it ended up how it did because it’s right in the middle of the movie, and it slows everything down, and it sells the naturalism and the performances even more because we aren’t using editing to tell the story. But it was a complete accident!

The last two shots of the movie are handheld close-up singles, first of the dad, then of Michael, and in each the actor is lit from frame left with a warm light and from frame right with a cooler cyan look. It suggests the duality that’s at play in each character, both in how they see one another and in how they see themselves. Am I reading more into it than was intended, or was this also part of your creative discussion with Alexa?

Weinstein: It totally was! I’m so glad you saw that. We wanted the complexity of what was going on internally to be mirrored in the lighting. We had been thinking of more of a green color, but we shot in a strip club called Mary’s in Portland, and it has these crazy cyan murals. We were really inspired by that color; it wasn’t so much this sickly green, but more like an alien blue-green that just felt right. Those shots sell the end of the movie. We wanted to make sure they had as much depth and as much conflict as was happening internally for the actors.

Your short films certainly offer an answer, but in your own words, what kinds of stories are you inspired to tell?

Weinstein: I’m fascinated by stories where people are desperately trying to connect but still end up missing each other. I’m fascinated by the human experience of trying to do the right thing and trying to be a good person but still causing hurt and pain and suffering. And I’m also passionate about telling queer stories. Right now I’m on a queer-history kick, telling stories of people in the past who lived lives much like we do today, bringing their adventures and loves and romances out into the world.

I think what film can do is communicate subconscious and incredibly small conflict and pain, and show us very minute and unrealized parts of ourselves. In both of these shorts, you see people who love each other desperately and deeply causing each other pain. Often the people who hurt us the most are the ones who love us the most; there’s this tragic miscommunication going on. I think most artists want to make the world a better place in some small way by telling stories, and I don’t quite know how to do that other than illuminating these little moments of human error and of a striving for connection that fails or misses the mark despite the deep and good intention behind the action.

What does it mean to you as a filmmaker to know you have the support of Panavision and Light Iron heading into your next project?

Weinstein: I’m so grateful. It came at a time of pandemic despair, and it’s made it all feel possible again. Before this grant, I was honestly feeling very nervous about making another movie because of what’s gone on in the world this year. I’ve been sitting on a bunch of ideas, unsure of what would come next, and this grant has inspired me to start writing another project. I’m not a hundred percent sure yet what I’ll do, but it’s inspired me in a huge way. It feels like an investment in my work as a filmmaker, and it makes me want to make another movie, whatever that ends up being.

All images courtesy of Em Weinstein.